Introduction to React

Published Feb 13, 2021

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- What is React?

- Why Should You Learn a Framework

- Reactivity

- Virtual DOM

- Let’s Talk About JSX

- Conclusion

Introduction

Are you thinking about learning React? Maybe you already have an eye on a course. I’m not here to decide that for you, but give you insight into React so you get more out of a course, or any free resource. A lot of content skips what I’m about to say, to the detriment of the learner.

This isn’t meant to cover prerequisite JavaScript knowledge you should know. If you’re looking for that, I recommend reading JavaScript to Know for React.

What is React?

A brief history.

After the ashes of Angular.js (not to be confused with Angular) transition to Angular 2 which was entirely a different framework to the ire of developers — many flocked to React in protest where it became and stayed one of the most popular frontend JavaScript frameworks.

Unlike Angular, Vue, or Svelte that are more opinionated (think of it as the swiss-army knife of frameworks) meaning they come with everything included out of the box such as state management, a router, perhaps a nice CLI (command-line interface) to bootstrap projects, and manage everything.

React took a different approach. It’s completely unopinionated about those things. It doesn’t include a router, state management, or animation library. This can lead to analysis paralysis when having to choose one yourself. You have to determine what a popular package is for what you need, and try it out. I think it’s a positive since you’re not limited to what the framework offers you.

Let’s back up a bit.

There’s a war waged on the internet. Is React a framework? The answer is simple; it’s not important. If you visit the React site it says “A JavaScript library for building user interfaces”. To me a library is something that you pull off the shelf, but isn’t integral to how your application works. Take for example Lodash that provides you with utility functions for making it easier to write code. React on the other hand — to be able to use it has to be included in your project.

React is just a humble library at ~2.8 kb. It consists of two parts. The first being the react package which is a diffing library (fancy term for some algorithm that is responsible to keep track of what changed, and perform an update based on that information). The other part is the react-dom package. A chonker at ~39.4 kb responsible for everything DOM (document object model) related, and is meant to be paired with the react package.

Interesting thing to note is that because React is just a diffing algorithm, we can use it on any device. That’s how React Native allows us to create native apps for Android, and iOS using React. Instead of using react-dom, where the DOM doesn’t make sense on a phone, it uses native components.

Why Should You Learn a Framework

If React is your first framework, this section is going to be enlightening.

If you wrote any JavaScript, then you know how repetitive, tedious and error-prone things such as DOM manipulation can be. You’re doing the same thing over and over. Everything is great on a fresh project, but soon enough things get out of hand. Your code becomes spaghetti. You might reach for a design pattern like OOP (object-oriented programming) to manage things easier. You also have to consider performance. Soon enough you’re going to write your own hacked together framework before you know — that you’re now responsible of maintaining.

The purpose of a framework is so you never have to touch the DOM, unless you have to. It makes writing code more declarative. That means things are abstracted so you don’t worry about implementation details. You can just focus on writing the logic.

A good example is the filter() method in JavaScript. It’s declarative since you don’t think how it’s implemented. You’re just able to use it. The opposite would be imperative, where you’d write your own logic that implements the same.

Let’s look at an example.

We’re going to display Pokemon with JavaScript, and compare it to the React equivalent. Not until we start, do we realize how something simple as that could not be so simple.

We have to consider a lot of things.

- Creation of DOM elements

- Populating each DOM element with content, and setting attributes

- Keeping state, and the user interface in sync

- We have to attach, and keep track of events listeners

Let’s pretend we got the Pokemon data from some API, database, or JSON file. I encourage you to type this code out yourself so you feel the burn. Try it out on Codepen, or whichever environment you prefer.

// state holds application data

let state = {

pokemon: ['Pikachu', 'Charmander', 'Bulbasaur'],

}

// create list to store our Pokemon

const pokemonEl = document.createElement('ul')

document.body.append(pokemonEl)

function showPokemon(pokemonList) {

if (state.pokemon.length < 1) {

document.body.innerHTML = '<p>There are no Pokemon to show.</p>'

return

}

// loop over each Pokemon, and append it to the list

for (const pokemonName of pokemonList) {

const pokemonNameEl = document.createElement('li')

pokemonNameEl.innerText = pokemonName

pokemonEl.append(pokemonNameEl)

}

}

function removePokemon(pokemonName) {

// remove Pokemon from the list

const filteredPokemon = state.pokemon.filter(

(pokemon) => pokemon !== pokemonName

)

// update state

state = {

pokemon: filteredPokemon,

}

// clear existing entries

pokemonEl.innerHTML = ''

// update user interface

showPokemon(state.pokemon)

}

// if we click on a Pokemon, remove it

pokemonEl.addEventListener('click', ({ target }) => {

if (target.tagName === 'LI') {

removePokemon(target.innerText)

}

})

showPokemon(state.pokemon)This is a lot of work already! Sure, we can abstract things further. We can create a nicer API for our developers — but now we’re responsible for maintaing a framework. We have to think about the implementation details, before writing “actual” code.

Notice also how we’re flushing the entire DOM, before we update it. We would have to implement logic that knows what element got removed, and only update that part in the DOM tree. Yikes! Only if there was a better way (cries out in infomercial).

Let’s look at the same example, done in React.

const pokemonData = ['Pikachu', 'Charmander', 'Bulbasaur']

function Pokemon() {

const [pokemon, setPokemon] = React.useState(pokemonData)

function removePokemon({ target }) {

const pokemonName = target.innerText

const filteredPokemon = pokemon.filter((pokemon) => pokemon !== pokemonName)

setPokemon(filteredPokemon)

}

if (pokemon.length < 1) {

return <p>There are no Pokemon to show.</p>

}

return (

<ul>

{pokemon.map((pokemonName) => (

<li key={pokemonName} onClick={removePokemon}>

{pokemonName}

</li>

))}

</ul>

)

}Even if you don’t know React yet, you can use your intuition since it’s just JavaScript. That’s what’s so great about React. There’s a couple of gotchas, but there’s not a lot of magic.

Notice how we didn’t have to do any of the tedious steps we had to do before. We just wrote our markup, and added JavaScript. Sure, there’s some “magic” React API we might not know about yet, but that’s fine.

The greatest benefit is that we have everything contained in one neat component. We can reuse this anywhere.

Reactivity

A big problem with our first example was having to keep our state, and user interface in sync. This is what frameworks do for us. Reactivity is a programming paradigm that allows us to adjust to changes in a declarative manner. In the React example, if the value of pokemon got changed it would rerender the component. You can find the most basic example of reactivity in a spreadsheet.

{% src=“reactivity-spreadsheet.mp4” %}

Taken from Vue docs which are awesome, and I hope React docs could learn from.

Virtual DOM

One thing I touched upon briefly was how we flushed the entire DOM for the list. With React we don’t have to. It just updates what changed. We talked earlier how that’s the entire point of the library. How does that work? It’s thanks to the virtual DOM. Think of it as a representation of the actual DOM in-memory. Once a change is made, React diffs it — and performs the update where needed.

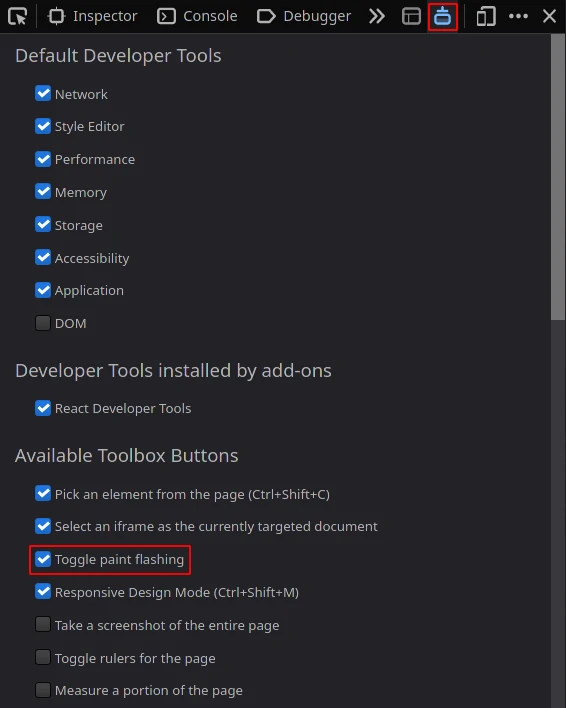

We can see this in the browser by enabling “Toggle paint flashing”. I’m using Firefox, but you can find the same feature in Chrome.

Here is the first example, using JavaScript.

The second example, using React.

This isn’t to say that using the virtual DOM is required. In fact, a framework like Svelte doesn’t even use it. The main takeaway is that this enables us to just write code, and not worry about performance implications.

Let’s Talk About JSX

Hope I didn’t lose you yet.

You might have noticed something that looks like HTML in our React code. That’s JSX (JavaScript XML). We can use our existing knowledge of HTML, with a few caveats which aren’t relevant here.

This is the key to understanding React. Let’s look at what JSX is, and not treat it like magic.

We can start writing React without any tooling! We just need to include a couple of scripts. We’re going to require react, react-dom, and babel packages. Babel is required to transform JSX, to something a browser can understand.

I suggest you do this local. Simply create a index.html file, and open it inside your browser.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="UTF-8" />

<title>React</title>

</head>

<body>

<div id="app"></div>

<script src="https://unpkg.com/react@17/umd/react.development.js"></script>

<script src="https://unpkg.com/react-dom@17/umd/react-dom.development.js"></script>

<script src="https://unpkg.com/babel-standalone@6/babel.min.js"></script>

<script type="text/babel">

function App() {

return <h1>Hello, World!</h1>

}

ReactDOM.render(<App />, document.getElementById('app'))

</script>

</body>

</html>Most React apps live inside a single div. That’s why they’re called single page applications. This means that JavaScript has complete control. It swaps out content on the fly. For example you can use an API to fetch some data, and display it. Because of that you can have static sites, that are dynamic. It’s also responsible for routing. We’re not going to go into those details.

The most important thing I want to talk about is JSX. Here lies the magic of understanding React. JSX might seem like magic at first, because we don’t see what’s going on under the hood. JSX is just JavaScript, and what you already know. Functions.

function App() {

return <h1>Hello, World!</h1>

}We can see how Babel transforms this, by using the Babel REPL. It’s simple as pasting in the code.

function App() {

return React.createElement('h1', null, 'Hello, World!')

}Just how JavaScript has document.createElement() to create elements, React has a similar API. It happens without you knowing it. It’s just JavaScript. The JSX syntax is just veneer, that gets turned into function calls. Once you grasp this concept, things start making a lot more sense.

The React.createElement() accepts three props. Type, props, and children. As you can see above, we’re not passing any props, so it’s null. Let’s say we’re receiving a textColor prop from another component. In React props are passed via a props object, so we can destructure it.

function App({ textColor: 'teal' }) {

return <h1 style={{ color: textColor }}>Hello, World!</h1>

}function App({ textColor: 'teal' }) {

return React.createElement('h1', {

style: {

color: textColor

}

}, 'Hello, World!')

}You’re going to understand things clearer, if you just think about what the actual code looks like. Let’s look how nested elements might look like.

function App() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Hello, World!</h1>

<p>Paragraph text</p>

</div>

)

}function App() {

return React.createElement(

'div',

null,

React.createElement('h1', null, 'Hello, World!'),

React.createElement('p', null, 'Paragraph text')

)

}What if we passed another component?

function Title({ children }) {

return <h1>{children}</h1>

}

function Paragraph({ children }) {

return <p>{children}</p>

}

function App() {

return (

<div>

<Title>Hello, World!</Title>

<Paragraph>Paragraph text</Paragraph>

</div>

)

}function Title({ children }) {

return React.createElement('h1', null, children)

}

function Paragraph({ children }) {

return React.createElement('p', null, children)

}

function App() {

return React.createElement(

'div',

null,

React.createElement(Title, null, 'Hello, World!'),

React.createElement(Paragraph, null, 'Paragraph text')

)

}children is just a special prop in React that passes any children to the component. By now you should get the hang of it, and if you don’t that’s okay. Use this as reference, the more you learn about React.

Conclusion

If you understand the underlying principles, and problems frameworks solve you can pick up any framework quickly. A framework is just a tool. If you don’t like React, that’s fine. You’re going to find one you do. When you do, consider learning how it works at a higher level. You don’t even have to open the source code.