The Complete Svelte 5 Course

Published Aug 14, 2025

Table of Contents

- What is Svelte?

- Try Svelte

- TypeScript Aside

- Single File Components

- Component Logic

- Markup Poetry

- Component Styles

- Svelte Reactivity

- Reactive State

- Deeply Reactive State

- Derived State

- Effects

- State In Functions And Classes

- Reactive Global State

- Why You Should Avoid Effects

- How Svelte Reactivity Works

- Using Template Logic

- Listening To Events

- Using Data Bindings

- Svelte Components

- Component Composition

- Transitions And Animations

- Using Third Party Libraries

- Special Elements

- Reactive Data Structures And Utilities

- Reactive Events

- Legacy Svelte

- Using Svelte With AI

What is Svelte?

If we read the definition from the Svelte website, it says:

Svelte is a UI framework that uses a compiler to let you write breathtakingly concise components that do minimal work in the browser, using languages you already know — HTML, CSS and JavaScript.

Because Svelte is a compiled language, it can wield the same syntax of a language that’s not great at making user interfaces like JavaScript and change the semantics for a better developer experience:

<script lang="ts">

// reactive state

let count = $state(0)

// reassignment updates the UI

setInterval(() => count += 1, 1000)

</script>

<p>{count}</p>You might think how Svelte does some crazy compiler stuff under the hood to make this work, but the output is human readable JavaScript:

function App($$anchor) {

// create signal

let count = state(0)

// update signal

setInterval(() => set(count, get(count) + 1), 1000)

// create element

var p = from_html(`<p> </p>`)

var text = child(p, true)

// update DOM when `count` changes

template_effect(() => set_text(text, get(count)))

// add to DOM

append($$anchor, p)

}Svelte’s reactivity is based on signals, so there’s nothing magical about it — you could write Svelte code without a compiler, but it would be tedious like writing JSX by hand using functions.

Just by reading the output code, you can start to understand how Svelte works. There’s no virtual DOM, or rerendering the component when state updates like in React — Svelte only updates the part of the DOM that changed.

This is what “does minimal work in the browser” means!

Svelte also has a more opinionated application framework called SvelteKit (equivalent to Next.js for React) if you need routing, server-side rendering, adapters to deploy to different platforms and so on.

Try Svelte

You can try Svelte in the browser using the Svelte Playground and follow along without having to set up anything.

If you’re a creature of comfort and prefer your development environment, you can scaffold a Vite project and pick Svelte as the option from the CLI if you run npm create vite@latest in a terminal — you’re going to need Node.js for that.

I also recommend using the Svelte for VS Code extension for syntax highlighting and code completion, or a similar extension for your editor.

TypeScript Aside

TypeScript has become table stakes when it comes to frontend development. For that reason, the examples are going to use TypeScript, but you can use JavaScript if you prefer.

If you’re unfamiliar with TypeScript, code after : usually represents a type. You can omit the types and your code will work:

// TypeScript 👍️

let items: string[] = [...]

// JavaScript 👍️

let items = [...]Some developers prefer writing JavaScript with JSDoc comments because it gives you the same benefits of TypeScript at the cost of a more verbose syntax:

/**

* This is a list of items.

* @type {string[]}

*/

let items = [...]That is completely up to you!

Single File Components

In Svelte, files ending with .svelte are called single file components because they contain the JavaScript, HTML, and CSS in a single file.

Here’s an example of a Svelte component:

<!-- logic -->

<script lang="ts">

let title = 'Svelte'

</script>

<!-- markup -->

<h1>{title}</h1>

<!-- styles -->

<style>

h1 {

color: orangered;

}

</style>A Svelte component can only have one top-level <script> and <style> block and is unique for every component instance. A code formatter like Prettier might arrange the blocks for you, but the order of the blocks doesn’t matter.

There’s also a special <script module> block used for sharing code across component instances we’ll learn about later.

Component Logic

Your component logic goes inside the <script> tag. Since Svelte 5, TypeScript is natively supported:

<script lang="ts">

let title = 'Svelte'

</script>

<h1>{title as string}</h1>Later we’re going to learn how you can even define values inside your markup, which can be helpful in some cases.

Markup Poetry

In Svelte, anything that’s outside the <script> and <style> blocks is considered markup:

<!-- markup -->

<h1>Svelte</h1>You can use JavaScript expressions in the template using curly braces and Svelte is going to evalute it:

<script lang="ts">

let banana = 1

</script>

<p>There's {banana} {banana === 1 ? 'banana' : 'bananas'} left</p>Later we’re going to learn about logic blocks like {#if ...} and {#each ...} to conditionally render content.

Tags with lowercase names are treated like regular HTML elements by Svelte and accept normal attributes:

<img src="image.gif" alt="Person dancing" />You can pass values to attributes using curly braces:

<script lang="ts">

let src = 'image.gif'

let alt = 'Person dancing'

</script>

<img src={src} alt={alt} />If the attribute name and value are the same, you can use a shorthand attribute:

<!-- 👍️ longhand -->

<img src={src} alt={alt} />

<!-- 👍️ shorthand -->

<img {src} {alt} />Attributes can have expressions inside the curly braces:

<script lang="ts">

let src = 'image.gif'

let alt = 'Person dancing'

let lazy = true

</script>

<img {src} {alt} loading={lazy ? 'lazy' : 'eager'} />You can spread objects on elements:

<script lang="ts">

let obj = {

src: 'image.gif',

alt: 'Person dancing'

}

</script>

<img {...obj} />To conditionally render attributes, use null or undefined instead of && for short-circuit evaluation and empty strings:

<script lang="ts">

let src = 'image.gif'

let alt = 'Person dancing'

let lazy = false

</script>

<!-- ⛔️ loading is `false` -->

<img {src} {alt} loading={lazy && 'lazy'} />

<!-- ⛔️ orphan attribute -->

<img {src} {alt} loading={lazy ? 'lazy' : ''} />

<!-- 👍 using `null` -->

<img {src} {alt} loading={lazy ? 'lazy' : null} />

<!-- 👍 using `undefined` -->

<img {src} {alt} loading={lazy ? 'lazy' : undefined} />Component Styles

There are many ways you can style a Svelte component. 💅 I’ve heard people love inline styles with Tailwind CSS, so you could just use the style tag…I’m joking! 😄

That being said, the style tag can be useful. You can use the style attribute like in regular HTML, but Svelte also has a shorthand style: directive you can use. The only thing you can’t pass is an object:

<script lang="ts">

let color = 'orangered'

</script>

<!-- 👍️ attribute -->

<h1 style="color: {color}">Svelte</h1>

<!-- 👍️ directive -->

<h1 style:color>Svelte</h1>

<!-- ⛔️ object -->

<h1 style={{ color }}>Svelte</h1>You can even add important like style:color|important to override styles. The style: directive is also great for CSS custom properties:

<script lang="ts">

let color = 'orangered'

</script>

<!-- 👍️ custom CSS property -->

<h1 style="--color: {color}">Svelte</h1>

<!-- 👍️ shorthand -->

<h1 style:--color={color}>Svelte</h1>

<style>

h1 {

/* custom CSS property with a default value */

color: var(--color, #fff);

}

</style>Scoped Styles

Fortunately, you’re not stuck using the style attribute. Most of the time, you’re going to use the style block to define styles in your component. Those styles are scoped to the component by default:

<h1>Svelte</h1>

<!-- these styles only apply to this component -->

<style>

h1 {

color: orangered;

}

</style>Scoped styles are unique to that component and don’t affect styles in other components. If you’re using the Svelte playground, you can open the CSS output tab to view the generated CSS:

/* uniquely generated class name */

h1.svelte-ep2x9j {

color: orangered;

}If you want to define global styles for your app, you can import a CSS stylesheet at the root of your app:

// inside a Vite project

import { mount } from 'svelte'

import App from './App.svelte'

import './app.css'

const app = mount(App, {

target: document.getElementById('app')!

})

export default appYou can also define global styles in components. This is useful if you have content from a content management system (CMS) that you have no control over.

Svelte has to “see” the styles in the component, so it doesn’t know they exist and warns you about removing unusued styles:

<script lang="ts">

let content = `

<h1>Big banana exposed</h1>

<p>The gorillas inside the banana cartel speak out</p>

`

</script>

<article>

{@html content}

</article>

<style>

article {

/* ⚠️ Unused CSS selector "h1" */

h1 {

text-transform: capitalize;

}

/* ⚠️ Unused CSS selector "p" */

p {

text-wrap: pretty;

}

}

</style>@html tag is used to render raw HTML in Svelte components. If you don't control the content, always sanitize user input to prevent XSS attacks.In that case, you can make the styles global by using the :global(selector) modifier:

<!-- ... -->

<style>

article {

:global(h1) {

text-transform: capitalize;

}

:global(p) {

text-wrap: pretty;

}

}

</style>Having to use :global on every selector is tedious! Thankfully, you can nest global styles inside a :global { ... } block:

<!-- ... -->

<style>

:global {

article {

h1 {

text-transform: capitalize;

}

p {

text-wrap: pretty;

}

}

}

</style>You can also have “global scoped styles” where the styles inside the :global block are scoped to the class:

<!-- ... -->

<style>

article :global {

h1 {

text-transform: capitalize;

}

p {

text-wrap: pretty;

}

}

</style>Here’s the compiled CSS output:

article.svelte-ju1yn8 {

h1 {

text-transform: capitalize;

}

p {

text-wrap: pretty;

}

}Keyframe animations are also scoped to the component. If you want to make them global, you have to prepend the keyframe name with -global-. The -global- part is removed when compiled, so you can reference the keyframe name in your app:

<style>

@keyframes -global-animation {

/* ... */

}

</style>You can use different preprocessors like PostCSS or SCSS by simply adding the lang attribute to the <style> tag with the preprocessor you want to use:

<style lang="postcss">

<!-- ... -->

</style>

<style lang="scss">

<!-- ... -->

</style>These days you probably don’t need SCSS anymore, since a lot of features such as nesting and CSS variables are supported by CSS.

Dynamic Classes

You can use an expression to apply a dynamic class, but it’s tedious and easy to make mistakes:

<script lang="ts">

let open = $state(false)

</script>

<button onclick={() => open = !open}>

<span>Accordion</span>

<span class="trigger {open ? 'open' : ''}">👈️</span>

</button>

<style>

.trigger {

display: inline-block;

transition: rotate 0.2s ease;

&.open {

rotate: -90deg;

}

}

</style>Thankfully, Svelte can helps us out here. You can use the class: directive to conditionally apply a class:

<span class="trigger" class:open>👈️</span>You can also pass an object, array, or both to the class attribute and Svelte is going to use clsx under the hood to merge the classes:

<!-- 👍️ passing an object -->

<span class={{ trigger: true, open }}>👈️</span>

<!-- 👍️ passing an array -->

<span class={['trigger', open && 'open']}>👈️</span>

<!-- 👍️ passing an array and object -->

<span class={['trigger', { open }]}>👈️</span>If you’re using Tailwind, this is very useful when you need to apply a bunch of classes:

<span class={['transition-transform', { '-rotate-90': open }]}>👈️</span>Also consider using data attributes for explicit transition states for easier orchestration, instead of using a bunch of classes:

<script lang="ts">

let status = $state('closed')

</script>

<span class="trigger" data-status={status}>👈️</span>

<style>

.trigger {

display: inline-block;

transition: rotate 0.2s ease;

&[data-status="closed"] {

rotate: 0deg;

}

&[data-status="open"] {

rotate: -90deg;

}

}

</style>Svelte Reactivity

In the context of JavaScript frameworks, application state refers to values that are essential to your application working and cause the framework to update the UI when changed.

Let’s look at a counter example:

<!-- only required for this example because of legacy mode -->

<svelte:options runes={true} />

<script lang="ts">

let count = 0

</script>

<button onclick={() => count += 1}>

{count}

</button>The Svelte compiler knows that you’re trying to update the count value and warns you because it’s not reactive:

countis updated, but is not declared with$state(...). Changing its value will not correctly trigger updates.

This brings us to our first Svelte rune — the $state rune.

Reactive State

The $state rune marks a variable as reactive. Svelte’s reactivity is based on assignments. To update the UI, you just assign a new value to a reactive variable:

<script lang="ts">

// reactive value

let count = $state(0)

</script>

<!-- reactive assignment -->

<button onclick={() => count += 1}>

Count: {count}

</button>You can open the developer tools and see that Svelte only updated the part of the DOM that changed.

count += 1 to emphasize assignment, but using count++ to increment the value also works.The $state(...) syntax is called a rune and is part of the language. It looks like a function, but it’s only a hint for the Svelte compiler to know what to do with it. This also means as far as TypeScript is concerned, it’s just a function:

let value = $state<Type>(...)The three main runes we’re going to learn about are the $state, $derived, and $effect rune.

Deeply Reactive State

If you pass an array, or object to $state it becomes a deeply reactive Proxy. This lets Svelte perform granular updates when you read or write properties and avoids mutating the state directly.

For example, changing editor.content is going to update the UI in every place where it’s used:

<script lang="ts">

let editor = $state({

theme: 'dark',

content: '<h1>Svelte</h1>'

})

</script>

<textarea

value={editor.content}

oninput={(e) => editor.content = (e.target as HTMLTextAreaElement).value}

spellcheck="false"

></textarea>

{@html editor.content}

<style>

textarea {

width: 600px;

height: 200px;

padding: 1rem;

border-radius: 0.5rem;

}

</style>$state.raw

You might not want deeply reactive state, where pushing to an array or updating the object would cause an update. In that case, you can use $state.raw so state only updates when you reassign it:

<script lang="ts">

// this could be a complex data structure

let editor = $state.raw({

theme: 'dark',

content: '<h1>Svelte</h1>'

})

</script>

<textarea

value={editor.content}

oninput={(e) => {

// ⛔️ can't be mutated

editor.content = e.target.value

// 👍️ reassignment

editor = {

...editor,

content: e.target.value

}

}}

spellcheck="false"

></textarea>

{@html editor.content}

<style>

textarea {

width: 100%;

height: 200px;

}

</style>$state.snapshot

Because proxied state is deeply reactive, you could change it on accident when you pass it around, or run into a problem with some API that doesn’t expect it. In that case, you can use $state.snapshot to get the normal value from the Proxy:

function saveEditorState(editor) {

// 💣️ oops! it doesn't like a Proxy object...

const editorState = structuredClone(editor)

// 👍️ normal object

const editorState = structuredClone($state.snapshot(editor))

}

// later

saveEditorState(editor)$state.snapshot when you console.log deeply reactive values for convenience.Destructuring

You can destructure deep state where you defined it — but if you destructure it anywhere else — it loses reactivity because it’s just JavaScript, so the values are evaluated when you destructure them:

<script lang="ts">

// 👍️ reactive

let { theme, content } = $state({

theme: 'dark',

content: '<h1>Svelte</h1>'

})

// ⛔️ not reactive

let { theme, content } = editor

</script>

{@html content}If you want to do this, you can use derived state!

Derived State

You can derive state from other state using the $derived rune and it’s going to reactively update:

<script lang="ts">

let count = $state(0)

let factor = $state(2)

let result = $derived(count * factor)

</script>

<p>{count} * {factor} = {result}</p>

<button onclick={() => count++}>Count: {count}</button>

<button onclick={() => factor++}>Factor: {factor}</button>Deriveds Only Update When They Change

Derived values only run when they’re read and are lazy evaluted which means they only update when they change, and not when their dependencies change to avoid unnecessary work.

Here even if max depends on count, it only updates when max updates:

<script lang="ts">

let count = $state(0)

let max = $derived(count >= 4)

// only logs when `max` changes

$inspect(max)

</script>

<button onclick={() => count++} disabled={max}>

{count}

</button>$inspect rune only runs in development and is great for seeing state updates and debugging.Derived Dependency Tracking

You can pass a function with state to a derived without losing reactivity:

<script lang="ts">

let count = $state(0)

let max = $derived(limit())

function limit() {

return count > 4 // 📖

}

</script>

<button onclick={() => count++} disabled={max}>

{count}

</button>This might sound like magic, but the only magic here is the system of signals and runtime reactivity! 🪄 In a later section, we’re going to learn how this exactly works.

The reason you don’t have to pass state to the function — unless you want to be explicit — is because signals only care where they’re read, as highlighted in the compiled output.

Passing state as argument:

let disabled = derived(() => limit(get(count))) // 📖

function limit(count) {

return count > 4

}Not passing any arguments:

let disabled = derived(limit())

function limit() {

return get(count) > 4 // 📖

}The only thing that matters is that count is read and tracked inside of an effect, so the limit function reruns when it updates.

$derived.by

The $derived rune only accepts an expression by default, but you can use the $derived.by rune for more complex derivations:

<script lang="ts">

let cart = $state([

{ item: '🍎', total: 10 },

{ item: '🍌', total: 10 }

])

let total = $derived.by(() => {

let sum = 0

for (let item of cart) {

sum += item.total

}

return sum

})

</script>

<p>Total: {total}</p>Svelte recommends you keep deriveds free of side-effects and you can’t update state inside of deriveds to protect you from unintended side-effects:

<script lang="ts">

let count = $state(0)

let double = $derived.by(() => {

// ⛔️ error

count++

})

</script>Destructuring From Deriveds

Going back to the previous example, you can also use derived state to keep reactivity when using destructuring:

<script lang="ts">

let editor = $state({

theme: 'dark',

content: '<h1>Svelte</h1>'

})

// ⛔️ not reactive

let { theme, content } = editor

// 👍️ reactive

let { theme, content } = $derived(editor)

</script>

{@html content}Effects

The last rune in the holy trinity of reactivity in Svelte you should know about is the $effect rune.

Effects are functions that run when the component is added to the DOM and when their dependencies change. State that is read inside of an effect will be tracked.

Here count is going to be logged when it updates, since it’s read inside of the effect and tracked as a dependency:

<script lang="ts">

let count = $state(0)

$effect(() => {

// 🕵️ tracked

console.log(count)

})

</script>

<button onclick={() => count++}>Click</button>Values are only tracked if they’re read — here if condition is true, then condition and count are going to be tracked, but if condition is false, then the effect only reruns when condition changes:

<script lang="ts">

let count = $state(0)

let condition = $state(false)

$effect(() => {

// 👍️ tracked

if (condition) {

// ⛔️ not tracked

console.log(count)

}

})

</script>

<button onclick={() => count++}>Click</button>

<button onclick={() => condition = !condition}>Toggle</button>You can return a function from the effect callback, which reruns when the effect dependencies change, or when the component is removed from the DOM.

Values that are read asynchronously like inside promises and timers are not tracked inside effects:

<script lang="ts">

let count = $state(0)

let delay = $state(1000)

$effect(() => {

// 🕵️ only `delay` is tracked

const interval = setInterval(() => count++, delay)

// 🧹 clear interval every update

return () => clearInterval(interval)

})

</script>

<button onclick={() => delay *= 2}>slower</button>

<span>{count}</span>

<button onclick={() => delay /= 2}>faster</button>Svelte provides an untrack function if you don’t want state to be tracked:

<script lang="ts">

import { untrack } from 'svelte'

let a = $state(0)

let b = $state(0)

$effect(() => {

// ⚠️ only logs when `b` changes

console.log(untrack(() => a) + b)

})

</script>

<button onclick={() => a++}>A</button>

<button onclick={() => b++}>B</button>Effect Dependency Tracking

When it comes to deeply reactive state, effects only rerun when the object it reads changes and not its properties:

<script lang="ts">

let obj = $state({ current: 0 })

let arr = $state([])

$effect(() => {

// ⛔️ not tracked

console.log(obj)

// 👍️ tracked

console.log(obj.current)

})

$effect(() => {

// ⛔️ not tracked

console.log(arr)

// 👍️ tracked

console.log(arr.length)

})

// later

obj.current++

arr.push(1)

</script>There are exceptions to the rule! If you use JSON.stringify or $state.snapshot, then everything is tracked:

<script lang="ts">

let obj = $state({ current: 0 })

let arr = $state([])

$effect(() => {

JSON.stringify(obj) // 👍️ tracked

})

$effect(() => {

JSON.stringify(arr) // 👍️ tracked

})

</script>When Not To Use Effects

In general, you should always avoid effects and never use effects to synchronize state, because Svelte queues your effects to ensure they run in the correct order and runs them last.

Using effects to synchronize state can cause unexpected behavior like state being out of sync:

<script lang="ts">

let count = $state(0)

let double = $state(0)

$effect(() => {

// effects run last

double = count * 2

})

</script>

<button onclick={() => {

count++ // 1

console.log(double) // ⚠️ 0

}}>

{double}

</button>Always derive state when you can instead:

<script lang="ts">

let count = $state(0)

let double = $derived(count * 2)

</script>

<button onclick={() => {

count++ // 1

console.log(double) // 👍️ 2

}}>

{double}

</button>If you want to do something when the component is added to the DOM and don’t care about tracking state, you can use the onMount lifecycle function instead of an effect:

<script lang="ts">

import { onMount } from 'svelte'

onMount(() => {

console.log('Component added 👋')

return () => console.log('🧹 Component removed')

})

</script>async callbacks to onMount and $effect as their cleanup won't run. You can use async functions, or an IIFE instead.When To Use Effects

Effects should be a last resort when you have to synchronize with an external system that doesn’t understand Svelte’s reactivity. They should only be used for side-effects like fetching data from an API, or working with the DOM directly.

In this example, we’re using the Pokemon API and getAbortSignal from Svelte to avoid making a bunch of requests when searching for a Pokemon:

<script lang="ts">

import { getAbortSignal } from 'svelte'

let pokemon = $state('charizard')

let image = $state('')

async function getPokemon(pokemon: string) {

const baseUrl = 'https://pokeapi.co/api/v2/pokemon'

const response = await fetch(`${baseUrl}/${pokemon}`, {

// aborts when derived and effect reruns

signal: getAbortSignal()

})

if (!response.ok) throw new Error('💣️ oops!')

return response.json()

}

$effect(() => {

getPokemon(pokemon).then(data => {

image = data.sprites.front_default

})

})

</script>

<input

type="search"

placeholder="Enter Pokemon name"

oninput={(e) => pokemon = (e.target as HTMLInputElement).value}

/>

<img src={image} alt={pokemon} />

<style>

input {

padding: 1rem;

border-radius: 1rem;

}

img {

width: 200px;

display: block;

margin-top: 1rem;

image-rendering: pixelated;

}

</style>$effect.pre

Your effects run after the DOM updates in a microtask, but sometimes you might need to do work before the DOM updates like measuring an element, or scroll position — in that case, you can use the $effect.pre rune.

Let’s look at an example that uses the GSAP Flip plugin to animate changes in the DOM and needs to measure the position, size, and rotation of elements before, and after the DOM update.

In this example, we measure the elements before the DOM updates, and use tick to wait for the DOM update:

<script lang="ts">

import { gsap } from 'gsap'

import { Flip } from 'gsap/Flip'

import { tick } from 'svelte'

gsap.registerPlugin(Flip)

let items = $state([...Array(10).keys()])

$effect.pre(() => {

// track `items` as a dependency

items

// measure elements before the DOM updates

const state = Flip.getState('.item')

// wait for the DOM update

tick().then(() => {

// do the FLIP animation

Flip.from(state, { duration: 1, stagger: 0.01, ease: 'power1.inOut' })

})

})

function shuffle() {

items = items.toSorted(() => Math.random() - 0.5)

}

</script>

<div class="container">

{#each items as item (item)}

<div class="item">{item}</div>

{/each}

</div>

<button onclick={shuffle}>Shuffle</button>

<style>

.container {

width: 600px;

display: grid;

grid-template-columns: repeat(5, 1fr);

gap: 0.5rem;

color: orangered;

font-size: 3rem;

font-weight: 700;

text-shadow: 2px 2px 0px #000;

.item {

display: grid;

place-content: center;

aspect-ratio: 1;

background-color: #222;

border: 1px solid #333;

border-radius: 1rem;

}

}

button {

margin-top: 1rem;

font-size: 2rem;

}

</style>tick function is a lifecyle function that uses the queueMicrotask method to schedule a task to run in the next microtask when all the work is done, and before the DOM updates.State In Functions And Classes

So far, we only used runes at the top-level of the component, but you can use state, deriveds, and effects inside functions and classes.

You can use runes in a JavaScript module by using the .svelte.js or .svelte.ts extension to tell Svelte that it’s a special file, so it doesn’t have to check every file for runes.

Here’s a createCounter function that holds and returns the count state:

export function createCounter(initial: number) {

let count = $state(initial)

return {

get count() { return count },

set count(v) { count = v }

}

}Here’s how it’s used inside of a Svelte component:

<script lang="ts">

import { createCounter } from './counter.svelte'

const counter = createCounter(0)

</script>

<button onclick={() => counter.count--}>-</button>

<span>{counter.count}</span>

<button onclick={() => counter.count++}>+</button>Reactive Properties

You’re probably wondering, what’s the deal with the get and set methods?

Those are called getters and setters, and they create accessor properties which let you define custom behavior when you read and write to a property.

They’re just part of JavaScript, and you could use functions instead:

export function createCounter(initial: number) {

let count = $state(initial)

return {

count() { return count },

setCount(v: number) { count = v }

}

}You could return a tuple instead to make the API nicer and destructure the read and write functions like let [count, setCount] = createCounter(0).

As you can see, the syntax is not as nice compared to using accessors, since you have to use functions everywhere:

<!-- using functions -->

<button onclick={() => counter.setCount(counter.count() + 1)}>

{counter.count()}

</button>

<!-- using accessors -->

<button onclick={() => counter.count++}>

{counter.count}

</button>Reactive Containers

The accessor syntax looks a lot nicer! 😄 You might be wondering, can’t you just return state from the function?

export function createCounter(initial: number) {

let count = $state(initial)

// ⛔️ this doesn't work

return { count }

}The reason this doesn’t work is because state is just a regular value and not some magic reactive container. If you want something like that, you could return deeply reactive proxied state:

export function createCounter(initial: number) {

let counter = $state({ count: initial })

// 👍️ proxied state

return counter

}You can create a reactive container if you want:

// reactive container utility

function reactive<T>(value: T) {

let state = $state<T>(value)

return state

}

function createCounter(initial: number) {

// reactive container

let counter = reactive({ count: initial })

return { counter }

}Even destructuring works, since counter is not just a regular value:

<script lang="ts">

import { createCounter } from './counter.svelte'

const { counter } = createCounter(0)

</script>

<button onclick={() => counter.count++}>

{counter.count}

</button>That seems super useful, so why doesn’t Svelte provide this utility?

It’s mostly because it’s a few lines of code, but another reason is classes. If you use state inside classes, you get extra benefits which you don’t get using functions.

Svelte turns any class fields declared with state into private fields with matching get/set methods, unless you declare them yourself:

export class Counter {

constructor(initial: number) {

// turned into `get`/`set` methods

this.count = $state(initial)

}

increment() {

this.count++

}

decrement() {

this.count--

}

}If you look at the output, you would see something like this:

class Counter {

#count

get count() { ... }

set count(v) { ... }

}There’s only one gotcha with classes and it’s how this works.

For example, using a method like counter.increment inside onclick doesn’t work, because this refers to where it was called:

<script lang="ts">

import { Counter } from './counter.svelte'

const counter = new Counter(0)

</script>

<button onclick={counter.decrement}>-</button>

<span>{counter.count}</span>

<button onclick={counter.increment}>+</button>You can see it for yourself:

increment() {

console.log(this) // button

this.count++

}

decrement() {

console.log(this) // button

this.count--

}You either have to pass an anonymous function like () => counter.increment() to onclick, or define the methods using arrow functions that don’t bind their own this:

increment = () =>

console.log(this) // class

this.current++

}

decrement = () => {

console.log(this) // class

this.current--

}The only downside with arrow functions is that you’re creating a new function every time time you call it, but everything works as expected.

Passing State Into Functions And Classes

Because state is a regular value, it loses reactivity when you pass it into a function or a class.

In this example, we pass count into Doubler to double the value when count updates. However, it’s not reactive since count is a regular value:

<script lang="ts">

class Doubler {

constructor(count: number) {

this.count = $derived(count * 2) // get(count) * 2

}

}

let count = $state(0)

const double = new Doubler(count) // get(count)

</script>

<button onclick={() => count++}>

{double.count}

</button>Svelte even gives you a warning with a hint:

This reference only captures the initial value of

count. Did you mean to reference it inside a closure instead?

To get the latest count value, we can pass a function instead:

<script lang="ts">

class Doubler {

constructor(count: () => number) {

this.count = $derived(count() * 2) // () => get(count) * 2

}

}

let count = $state(0)

const double = new Doubler(() => count) // () => get(count)

</script>

<button onclick={() => count++}>

{double.count}

</button>Also, we already have a reactive Counter class we can use:

<script lang="ts">

class Counter {

constructor(initial: number) {

this.count = $state(initial)

}

}

class Doubler {

constructor(counter: Counter) {

this.count = $derived(counter.count * 2)

}

}

const counter = new Counter(0)

const double = new Doubler(counter)

</script>

<button onclick={() => counter.count++}>

{double.count}

</button>Runes are reactive primitives that give you the flexibility to create your own reactivity system.

Reactive Global State

Creating global reactive state in Svelte is simple as exporting deep state from a module, like a config which can be used across your app:

interface Config {

theme: 'light' | 'dark'

}

export const config = $state<Config>({ theme: 'dark' })

export function toggleTheme() {

config.theme = config.theme === 'light' ? 'dark' : 'light'

}<script>

import { config, toggleTheme } from './config.svelte'

</script>

<button onclick={toggleTheme}>

{config.theme}

</button>You could use a function, or a class for the config:

type Themes = 'light' | 'dark'

class Config {

theme = $state<Themes>('dark')

toggleTheme() {

this.theme = this.theme === 'light' ? 'dark' : 'light'

}

}

export const config = new Config()It doesn’t matter if you use functions or classes, as long as you understand how Svelte reactivity works.

Why You Should Avoid Effects

I don’t want to scare you from using effects. Honestly, it’s not a big deal if you sometimes use effects when you shouldn’t.

It’s unlikely your app would be worse just by using effects — the actual problem is that it’s easy to overcomplicate your code with effects, because it seems like the right thing to do.

In this example, we’re using the Web Storage API to read and write the counter value each time it updates. Hey, that’s a side-effect! Using an effect seems resonable:

class Counter {

constructor(initial: number) {

this.count = $state(initial)

$effect(() => {

const savedCount = localStorage.getItem('count')

if (savedCount) this.count = parseInt(savedCount)

})

$effect(() => {

localStorage.setItem('count', this.count.toString())

})

}

}The problem only arises if you create the counter outside the component initialization phase (in a separate module, or inside of an event handler):

export const counter = new Counter(0)Oops! Immediately, there’s an effect_orphan error:

$effectcan only be used inside an effect (e.g. during component initialisation).

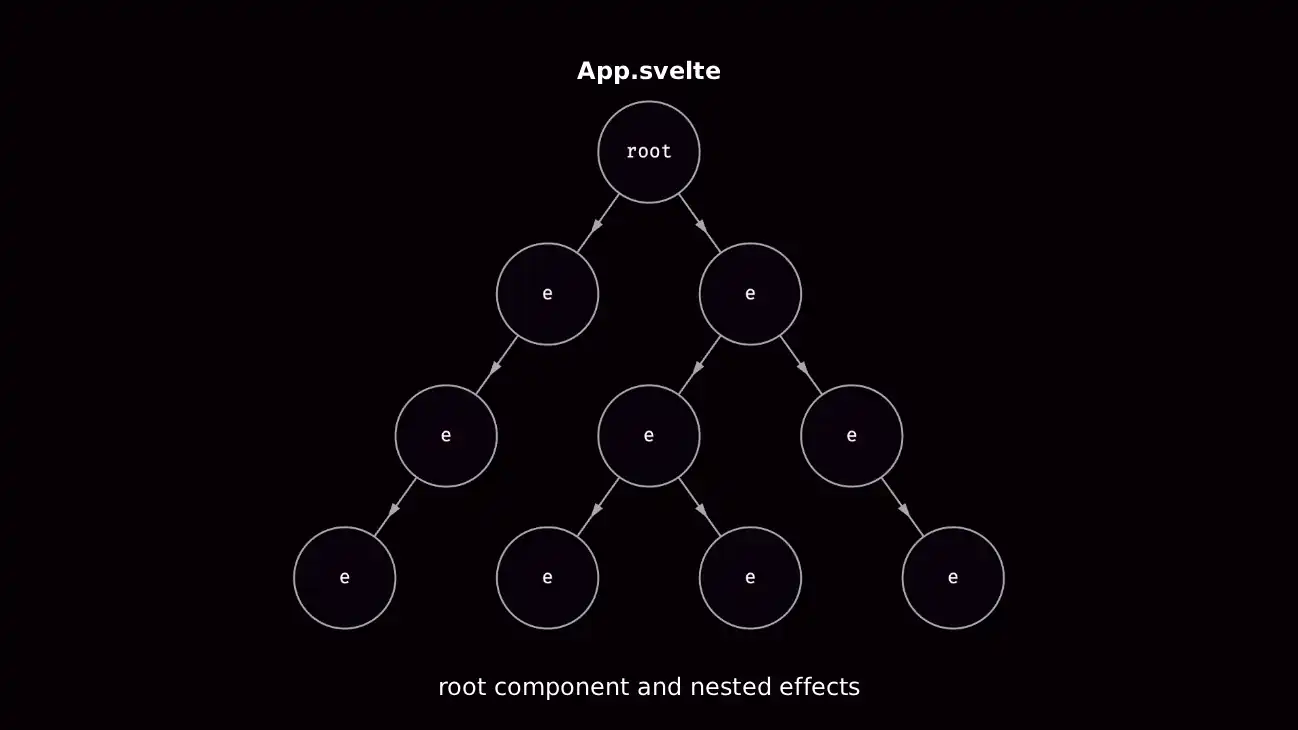

Your entire app is a root effect with other nested effects, so Svelte can run the teardown logic for them when the component is removed — in this case, you’re trying to create an effect outside that root effect, so Svelte can’t keep track of it.

Svelte provides an advanced $effect.root rune to create your own root effect, but now you have to run the cleanup manually:

class Counter {

#cleanup

constructor(initial: number) {

this.count = $state(initial)

// manual cleanup 😮💨

this.cleanup = $effect.root(() => {

$effect(() => {

const savedCount = localStorage.getItem('count')

if (savedCount) this.count = parseInt(savedCount)

})

$effect(() => {

localStorage.setItem('count', this.count.toString())

})

return () => console.log('🧹 cleanup')

})

}

destroy() {

this.#cleanup()

}

}Awkward! 😄 Then you learn about the $effect.tracking rune, used to know if you’re inside a tracking context like the effect in your template, so maybe that’s the solution?

class Counter {

constructor(initial: number) {

this.count = $state(initial)

if ($effect.tracking()) {

$effect(() => {

const savedCount = localStorage.getItem('count')

if (savedCount) this.count = parseInt(savedCount)

})

$effect(() => {

localStorage.setItem('count', this.count.toString())

})

}

}

}But there’s another problem! The effect is never going to run when the counter is created, because you’re not inside a tracking context. 😩

It would make more sense to move the effect where you read the value — this way, it’s read inside of a tracking context like the template effect:

export class Counter {

constructor(initial: number) {

this.#count = $state(initial)

}

get count() {

if ($effect.tracking()) {

$effect(() => {

const savedCount = localStorage.getItem('count')

if (savedCount) this.#count = parseInt(savedCount)

})

}

return this.#count

}

set count(v: number) {

localStorage.setItem('count', v.toString())

this.#count = v

}

}There’s another problem. Each time we read the value, we’re creating an effect! 😨 That’s a simple fix — we can use a variable to track if we already ran the effect:

export class Counter {

#first = true

constructor(initial: number) {

this.#count = $state(initial)

}

get count() {

if ($effect.tracking()) {

$effect(() => {

if (!this.#first) return

const savedCount = localStorage.getItem('count')

if (savedCount) this.#count = parseInt(savedCount)

this.#first = false

})

}

return this.#count

}

set count(v: number) {

localStorage.setItem('count', v.toString())

this.#count = v

}

}In reality, none of this is necessary — you can make everything simpler by doing side-effects inside event handlers like onclick instead of using effects. In fact, we can just remove the effect and everything works:

export class Counter {

#first = true

constructor(initial: number) {

this.#count = $state(initial)

}

get count() {

if (this.#first) {

const savedCount = localStorage.getItem('count')

if (savedCount) this.#count = parseInt(savedCount)

this.#first = false

}

return this.#count

}

set count(v: number) {

localStorage.setItem('count', v.toString())

this.#count = v

}

}Unless you know what you’re doing — if you catch yourself using advanced runes like $effect.root or $effect.tracking, you’re doing something wrong.

How Svelte Reactivity Works

I believe that understanding how something works gives you greater enjoyment in life by being more competent at what you do.

I mentioned how Svelte uses signals for reactivity, but so do many other frameworks like Angular, Solid, Vue, and Qwik. There’s even a proposal to add signals to JavaScript itself.

So far we learned that reassignments cause updates in Svelte. There’s nothing special about = though! It just creates a function call to update the value:

<script lang="ts">

let value = $state('🍎')

value = '🍌' // set(value, '🍌')

</script>

<!-- how does this get updated? -->

{value}A signal is just a container that holds a value and subscribers that are notified when that value updates, so it doesn’t do anything on its own:

function state(value) {

const signal = { value, subscribers: new Set() }

return signal

}You need effects to react to signals and effects are just functions that run when a signal updates.

That’s how Svelte updates the DOM by compiling your template into effects. This is referred to as a tracking context:

template_effect(() => set_text(text, get(value)))Your entire app is a root effect with nested effects inside of it, so Svelte can keep track of your effects for cleanup. When the effect runs, it invokes the callback function and sets it as the active effect in some variable:

let activeEffect = null

function effect(fn) {

// set active effect

activeEffect = fn

// run the effect

fn()

}The magic happens when you read a signal inside of an effect. When value is read, it adds the active effect as a subscriber:

// the active effect

let activeEffect = fn

function get(signal) {

// add effect to subscribers

signal.subscribers.add(activeEffect)

// return value

return signal.value

}Later, when you write to count it notifies the subscribers and recreates the dependency graph when it reads the signal inside the effect:

function set(signal, value) {

// update signal

signal.value = value

// notify subscribers

signal.subscribers.forEach(effect => effect())

}You can just update state and it’s going to update the UI anywhere where it’s used. If you’re familiar with the observer pattern, signals are observables on steroids and frameworks like Svelte do a lot of work under the hood to make them performant.

Here’s a counter example using our basic signals implementation inside a regular .html file:

<script type="module">

import { state, set, get, effect } from './signals.js'

// create signal

const count = state(0)

// hook into DOM elements

const btn = document.querySelector('button')

btn.onclick = () => set(count, get(count) + 1)

// create template effect

effect(() => btn.textContent = get(count))

</script>

<button>0</button>This is oversimplified, but it happens every update and that’s why it’s called runtime reactivity, because it happens as your code runs!

Svelte doesn’t compile reactivity, it only compiles the implementation details. That’s how you can use signals like a regular value. In other frameworks, you always have to read and write them using functions, or accessors.

Deriveds are effects that track their own dependencies and return a signal — you can pass a function with state inside to a derived, and it’s tracked when it’s read inside like an effect:

<script lang="ts">

let value = $state('🍎')

let code = $derived(getCodePoint())

function getCodePoint() {

// `value` is read inside the derived effect

return value.codePointAt(0).toString(16)

}

value = '🍌'

</script>

<!-- `code` is read inside the template effect -->

{code}I want to emphasize how $state is not some magic reactive container, but a regular value; which is why you need a function or a getter to get the latest value when the effect reruns — unless you’re using deep state.

Here if emoji.code was a regular value and not a getter, the text inside the button would never update:

<script lang="ts">

class Emoji {

constructor(emoji: string) {

// turned into `get` and `set` methods

this.current = $state(emoji)

this.code = $derived(this.current.codePointAt(0).toString(16))

}

}

const emoji = new Emoji('🍎')

</script>

<button onclick={() => emoji.current = '🍌'}>

<!-- template_effect(() => set_text(text, emoji.code)) -->

{emoji.code}

</button>As the React people love to say, “it’s just JavaScript!” 😄

Using Template Logic

HTML doesn’t have conditionals or loops, but Svelte has control flow blocks ranging from {#if ...}, {#each ...} to data loading blocks like {#await ...}.

Using Conditionals

In Svelte, you can use the {#if ...} block to conditionally render content:

<script lang="ts">

type Status = 'loading' | 'success' | 'error'

let status = $state<Status>('loading')

</script>

{#if status === 'loading'}

<p>Loading...</p>

{:else if status === 'success'}

<p>Success!</p>

{:else if status === 'error'}

<p>Error</p>

{:else}

<p>Impossible state</p>

{/if}Looping Over Data

To loop over a list of items, you use the {#each ...} block:

<script lang="ts">

let todos = $state([

{ id: 1, text: 'Todo 1', done: false },

{ id: 2, text: 'Todo 2', done: false },

{ id: 3, text: 'Todo 3', done: false },

{ id: 4, text: 'Todo 4', done: false }

])

</script>

<ul>

{#each todos as todo}

<li>

<input checked={todo.done} type="checkbox" />

<span>{todo.text}</span>

</li>

{:else}

<p>No items</p>

{/each}

</ul>You can destructure the value you’re iterating over, get the current item index, and provide a unique key so Svelte can keep track of changes:

<ul>

{#each todos as { id, text, done }, i (id)}

<li>

<input checked={done} type="checkbox" />

<span style:color={i % 2 === 0 ? 'orangered' : ''}>{text}</span>

</li>

{/each}

</ul>You can omit the as part inside the {#each ...} block when you just want to loop over an arbitrary amount of items. In this example, we’re creating a basic grid:

<div class="grid">

{#each Array(10), row}

{#each Array(10), col}

<div class="cell">{row},{col}</div>

{/each}

{/each}

</div>

<style>

.grid {

max-width: 400px;

display: grid;

grid-template-columns: repeat(10, 1fr);

gap: 0.5rem;

.cell {

padding: 1rem;

border: 1px solid #ccc;

}

}

</style>You can loop over any iterable that works with Array.from from a Map and Set object, to generators:

<script lang="ts">

let itemsMap = new Map([

['🍎', 'apple'],

['🍌', 'banana'],

])

let itemsSet = new Set(['🍎', '🍌'])

function* itemsGenerator() {

yield '🍎'

yield '🍌'

}

</script>

<ul>

{#each itemsMap as [key, value]}

<li>{key}: {value}</li>

{/each}

</ul>

<ul>

{#each itemsSet as item}

<li>{item}</li>

{/each}

</ul>

<ul>

{#each itemsGenerator() as item}

<li>{item}</li>

{/each}

</ul>Svelte even has reactive versions of built-in JavaScript objects, which we’re going to look at later.

Asynchronous Data Loading

Previously, we fetched some pokemon data inside of an effect, but we haven’t handled the loading, error, or success state.

Svelte has an {#await ...} block for dealing with promises which handles loading, error, and success states:

<script lang="ts">

async function getPokemon(pokemon: string) {

const baseUrl = 'https://pokeapi.co/api/v2/pokemon'

const response = await fetch(`${baseUrl}/${pokemon}`)

if (!response.ok) throw new Error('💣️ oops!')

let { name, sprites } = await response.json()

return { name, image: sprites['front_default'] }

}

</script>

{#await getPokemon('charizard')}

<p>loading...</p>

{:then pokemon}

<p>{pokemon.name}</p>

<img src={pokemon.image} alt={pokemon.name} />

{:catch error}

<p>{error.message}</p>

{/await}You can omit the catch block if you don’t care about errors, and the initial block if you only care about the result:

{#await getPokemon('charizard') then pokemon}

<p>{pokemon.name}</p>

<img src={pokemon.image} alt={pokemon.name} />

{/await}Asynchronous Svelte Aside

In the near future, you’re going to be able to await a promise directly in a Svelte component. You can try it today by enabling the experimental async flag in your Svelte config:

export default {

compilerOptions: {

experimental: {

async: true

}

}

}At the moment you have to create a boundary at the root of your app, or where you want to use the await keyword:

<script lang="ts">

let { children } = $props()

</script>

<svelte:boundary>

{#snippet pending()}

<!-- only shows when the component is added -->

<p>loading...</p>

{/snippet}

{@render children?.()}

</svelte:boundary>Then inside of a component, you can use the await keyword in the script block, or template:

<script lang="ts">

// same Pokemon API as before

import { getPokemon } from './pokemon.ts'

let pokemon = await getPokemon('charizard')

</script>

<p>{pokemon.name}</p>

<img src={pokemon.image} alt={pokemon.name} />You can use the $effect.pending rune to show a loading state:

<!-- shows when loading new data -->

{#if $effect.pending()}

<p>loading...</p>

{:else}

<p>{(await pokemon).name}</p>

<img src={(await pokemon).image} alt={(await pokemon).name} />

{/if}SvelteKit takes this even further with remote functions where you can call remote functions like regular functions in the client, with type-safety across the server and client.

Recreating Elements

You can use the {#key ...} block to recreate elements when state updates. This is useful for replaying transitions, which we’re going to learn about later:

<script lang="ts">

import { fade } from 'svelte/transition'

let value = $state(0)

</script>

{#key value}

<div in:fade>👻</div>

{/key}

<button onclick={() => value++}>Spook</button>Local Constants

You can use the @const tag to define block-scoped readonly local constants in the Svelte template.

Local constants can only be defined as a child of blocks like {#if ...}, {#else ...}, {#await ...}, and <Component />.

In this example, we can destructure text and done from the todo object while keeping the original reference:

<ul>

{#each todos as todo}

{@const { text, done: checked } = todo}

<li>

<input {checked} type="checkbox" />

<span>{text}</span>

</li>

{/each}

</ul>In this example, we’re creating a SVG grid using local constants to keep everything organized and legible:

<script lang="ts">

let size = 800

let tiles = 8

</script>

<svg width={size} height={size}>

{#each Array(tiles), col}

{#each Array(tiles), row}

{@const tile = size / tiles}

{@const x = col * tile}

{@const y = row * tile}

{@const width = tile}

{@const height = tile}

{@const fill = (col + row) % 2 === 0 ? 'orangered' : 'white'}

<rect {x} {y} {width} {height} {fill} />

{/each}

{/each}

</svg>Listening To Events

You can listen to DOM events by adding attributes that start with on to elements. In the case of a mouse click, you would add the onclick attribute to a <button> element:

<script lang="ts">

function onclick() {

console.log('clicked')

}

</script>

<!-- using an inline function -->

<button onclick={() => console.log('clicked')}>Click</button>

<!-- passing a function -->

<button onclick={onclick}>Click</button>

<!-- using the shorthand -->

<button {onclick}>Click</button>You can spread events, since they’re just attributes:

<script lang="ts">

const events = {

onclick: () => console.log('clicked'),

ondblclick: () => console.log('double clicked')

}

</script>

<button {...events}>Click</button>This example uses the onmousemove event to update the mouse position:

<script lang="ts">

let mouse = $state({ x: 0, y: 0 })

// the event is automatically passed

function onmousemove(e: MouseEvent) {

mouse.x = e.clientX

mouse.y = e.clientY

}

</script>

<div {onmousemove}>

The mouse position is {mouse.x} x {mouse.y}

</div>

<style>

div {

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

}

</style>You can prevent the default behavior by using e.preventDefault(). This is useful for things like when you want to control a form with JavaScript and avoid a page reload:

<script lang="ts">

function onsubmit(e: SubmitEvent) {

e.preventDefault()

const data = new FormData(this)

const email = data.get('email')

console.log(email)

}

</script>

<form {onsubmit}>

<input type="email" name="email" />

<button type="submit">Subscribe</button>

</form>Using Data Bindings

In JavaScript, it’s common to listen for the user input on the <input> element through the input event, and update a value. This is called one-way data binding since updating the value doesn’t update the input. In Svelte, you can use the bind: directive to keep them in sync.

Two-Way Data Binding

Having to do value={search} and oninput={(e) => search = e.target.value} on the <input> element to update search is mundane for something you do often:

<script lang="ts">

let list = $state(['Angular', 'React', 'Solid', 'Svelte', 'Vue', 'Qwik'])

let filteredList = $derived(list.filter((item) => item.includes(search)))

let search = $state('')

</script>

<input

type="search"

placeholder="Search"

value={search}

oninput={(e) => search = (e.target as HTMLInputElement).value}

/>

<ul>

{#each filteredList as item}

<li>{item}</li>

{:else}

<p>No results</p>

{/each}

</ul>Thankfully, Svelte supports two-way data binding using the bind: directive. If you update the value, it updates the input and vice versa:

<input type="search" bind:value={search} ... />One of the more useful bindings is bind:this to get a reference to a DOM node such as the <canvas> element for example:

<script lang="ts">

// this is `undefined` until the component is added

let canvas: HTMLCanvasElement

$effect(() => {

// ⛔️ don't do this

const canvas = document.querySelector('canvas')!

// 👍️ bind the value instead

const ctx = canvas.getContext('2d')

})

</script>

<canvas bind:this={canvas}></canvas>Function Bindings

Another useful thing to know about are function bindings if you need to validate some input, or link one value to another.

This example transforms the text the user types into the Mocking SpongeBob case:

<script lang="ts">

let text = $state('I love Svelte')

function toSpongeBobCase(text: string) {

return text

.split('')

.map((c, i) => i % 2 === 1 ? c.toUpperCase() : c.toLowerCase())

.join('')

}

</script>

<textarea

value={toSpongeBobCase(text)}

oninput={(e) => {

text = toSpongeBobCase((e.target as HTMLInputElement).value)

}}

></textarea>

<style>

textarea {

width: 600px;

height: 300px;

padding: 1rem;

border-radius: 0.5rem;

}

</style>Instead of passing an expression like bind:property={expression}, you can pass a function binding like bind:property={get, set} to have more control over what happens when you read and write a value:

<!-- ... -->

<textarea

bind:value={

() => toSpongeBobCase(text),

(v: string) => text = toSpongeBobCase(v)

}

></textarea>Readonly Bindings

Svelte provides two-way bindings, and readonly bindings for different elements you can find in the Svelte documentation for bind.

There are media bindings for <audio>, <video>, and <img> elements:

<script lang="ts">

let clip = 'video.mp4'

let currentTime = $state(0)

let duration = $state(0)

let paused = $state(true)

</script>

<div class="container">

<video src={clip} bind:currentTime bind:duration bind:paused></video>

<div class="controls">

<button onclick={() => paused = !paused}>

{paused ? '▶️' : '⏸️'}

</button>

<span>{currentTime.toFixed(1)}/{duration.toFixed(1)}</span>

<input type="range" bind:value={currentTime} max={duration} step={0.1} />

</div>

</div>

<style>

.container {

width: 600px;

video {

width: 100%;

border-radius: 0.5rem;

}

.controls {

display: flex;

gap: 0.5rem;

input[type="range"] {

flex-grow: 1;

}

}

}

</style>There are also readonly bindings for visible elements that use ResizeObserver to measure any dimension changes:

<script lang="ts">

let width = $state()

let height = $state()

</script>

<div class="container" bind:clientWidth={width} bind:clientHeight={height}>

<div class="text" contenteditable>Edit this text</div>

<div class="size">{width} x {height}</div>

</div>

<style>

.container {

position: relative;

display: inline-block;

padding: 0.5rem;

border: 1px solid orangered;

.text {

font-size: 2rem;

}

.size {

position: absolute;

left: 50%;

bottom: 0px;

padding: 0.5rem;

translate: -50% 100%;

color: black;

background-color: orangered;

font-weight: 700;

white-space: pre;

}

}

</style>In the next section we’re going to learn about components and how we can also bind the properties we pass to them, making the data flow from child to parent.

Svelte Components

Frameworks are not tools for organizing your code, they are tools for organizing your mind. — Rich Harris

A Svelte component is a file that ends with a .svelte extension. You can think of components as blocks that include the markup, styles, and logic that can be used across your app, and can be combined with other blocks.

Let’s use a basic todo list app as an example:

<script lang="ts">

import { slide } from 'svelte/transition'

type Todo = { id: string; text: string; completed: boolean }

type Filter = 'all' | 'active' | 'completed'

let todo = $state('')

let todos = $state<Todo[]>([])

let filter = $state<Filter>('all')

let filteredTodos = $derived(filterTodos())

let remaining = $derived(remainingTodos())

function addTodo(e: SubmitEvent) {

e.preventDefault()

todos.push({

id: crypto.randomUUID(),

text: todo,

completed: false

})

todo = ''

}

function removeTodo(todo: Todo) {

todos = todos.filter((t) => t.id !== todo.id)

}

function filterTodos() {

return todos.filter((todo) => {

if (filter === 'all') return true

if (filter === 'active') return !todo.completed

if (filter === 'completed') return todo.completed

})

}

function setFilter(newFilter: Filter) {

filter = newFilter

}

function remainingTodos() {

return todos.filter((todo) => !todo.completed).length

}

function clearCompleted() {

todos = todos.filter((todo) => !todo.completed)

}

</script>

<form onsubmit={addTodo}>

<input type="text" placeholder="Add todo" bind:value={todo} />

</form>

<ul>

{#each filteredTodos as todo (todo)}

<li transition:slide>

<input type="checkbox" bind:checked={todo.completed} />

<input type="text" bind:value={todo.text} />

<button onclick={() => removeTodo(todo)}>🗙</button>

</li>

{/each}

</ul>

<div>

<p>{remaining} {remaining === 1 ? 'item' : 'items'} left</p>

<div class="filters">

{#each ['all', 'active', 'completed'] as const as filter}

<button onclick={() => setFilter(filter)}>{filter}</button>

{/each}

<button onclick={clearCompleted}>Clear completed</button>

</div>

</div>Let’s take the contents of the Todos.svelte file and break it into multiple components. You can keep everything organized and place the files inside a todos folder:

todos/

├── Todos.svelte

├── AddTodo.svelte

├── TodoList.svelte

├── TodoItem.svelte

└── TodoFilter.svelteComponent have to use a capitalized tag such as <Component>, or dot notation like <my.component>. How you name the file is irrelevant, but most often you’re going to see PascalCase, so that’s what I’m going to use. Personally, I prefer kebab-case.

Let’s create the <AddTodo> component that’s going to handle adding a new todo. To pass data from one component to another, we use properties, or props for short — similar to how you pass attributes to elements.

To receive the props, we use the $props rune:

<script lang="ts">

interface Props {

todo: string

addTodo: () => void

}

let props: Props = $props()

</script>

<form onsubmit={props.addTodo}>

<input type="text" placeholder="Add todo" bind:value={props.todo} />

</form>You can destructure props, rename them, set a default value, and spread the rest of the props:

<script lang="ts">

interface Props {

todo: string

addTodo: () => void

}

let { addTodo, todo = 'Fallback', ...props }: Props = $props()

</script>

<form onsubmit={addTodo} {...props}>

<input type="text" placeholder="Add todo" bind:value={todo} />

</form>To update todo from the child component, we have to let Svelte know it’s okay for the child to mutate the parent state by using the $bindable rune:

<script lang="ts">

interface Props {

todo: string

addTodo: () => void

}

let { addTodo, todo = $bindable('Fallback') } = $props()

</script>

<form onsubmit={addTodo}>

<input type="text" placeholder="Add todo" bind:value={todo} />

</form>You can now safely bind the todo prop:

<script lang="ts">

import AddTodo from './AddTodo.svelte'

let todo = $state('')

// ...

</script>

<AddTodo {addTodo} bind:todo />In reality, you don’t have to do this. It makes more sense to move the todo state inside <AddTodo>and use a callback prop to change it:

<script lang="ts">

function addTodo(todo: string) {

todos.push({

id: crypto.randomUUID(),

text: todo,

completed: false

})

}

// ...

</script>

<AddTodo {addTodo} />Let’s update the <AddTodo> component:

<script lang="ts">

interface Props {

addTodo: (todo: string) => void

}

let { addTodo }: Props = $props()

let todo = $state('')

function onsubmit(e: SubmitEvent) {

e.preventDefault()

addTodo(todo)

todo = ''

}

</script>

<form {onsubmit}>

<input type="text" placeholder="Add todo" bind:value={todo} />

</form>You can submit the todo by pressing enter, and it won’t reload the page. Instead of binding the value, you can also get the value from the form onsubmit event.

Let’s create the <TodoList> component to render the list of todos, and use a Svelte transition to spice it up:

<script lang="ts">

import { slide } from 'svelte/transition'

interface Props {

todos: { id: number; text: string; completed: boolean }[]

removeTodo: (id: number) => void

}

let { todos, removeTodo }: Props = $props()

</script>

<ul>

{#each todos as todo, i (todo)}

<li transition:slide>

<input type="checkbox" bind:checked={todo.completed} />

<input type="text" bind:value={todo.text} />

<button onclick={() => removeTodo(todo.id)}>🗙</button>

</li>

{/each}

</ul>Let’s pass the filteredTodos and removeTodo props:

<script lang="ts">

import AddTodo from './AddTodo.svelte'

import TodoList from './TodoList.svelte'

// ...

</script>

<AddTodo {todo} {addTodo} />

<TodoList todos={filteredTodos} {removeTodo} />Let’s create the <TodoFilter> component to filter the todos:

<script lang="ts">

type Filter = 'all' | 'active' | 'completed'

interface Props {

remaining: number

setFilter: (filter: Filter) => void

clearCompleted: () => void

}

let { remaining, setFilter, clearCompleted }: Props = $props()

</script>

<div>

<p>{remaining} {remaining === 1 ? 'item' : 'items'} left</p>

<div class="filters">

{#each ['all', 'active', 'completed'] as const as filter}

<button onclick={() => setFilter(filter)}>{filter}</button>

{/each}

<button onclick={clearCompleted}>Clear completed</button>

</div>

</div>Let’s pass the remaining, setFilter, and clearCompleted props:

<script lang="ts">

import AddTodo from './AddTodo.svelte'

import TodoList from './TodoList.svelte'

import TodoFilter from './TodoFilter.svelte'

// ...

</script>

<AddTodo {todo} {addTodo} />

<TodoList todos={filteredTodos} {removeTodo} />

<TodoFilter {remaining} {setFilter} {clearCompleted} />I left the <TodoItem> component for last to show the downside of abusing bindings:

<script lang="ts">

import { slide } from 'svelte/transition'

interface Props {

todo: { id: number; text: string; completed: boolean }

removeTodo: (id: number) => void

}

let { todo = $bindable(), removeTodo }: Props = $props()

</script>

<li transition:slide>

<input type="checkbox" bind:checked={todo.completed} />

<input type="text" bind:value={todo.text} />

<button onclick={() => removeTodo(todo.id)}>🗙</button>

</li>This works, but you’re going to get warnings for mutating todos in the parent state if you don’t make todos bindable:

<script lang="ts">

import AddTodo from './AddTodo.svelte'

import TodoList from './TodoList.svelte'

import TodoFilter from './TodoFilter.svelte'

// ...

</script>

<AddTodo {todo} {addTodo} />

<TodoList bind:todos={filteredTodos} {removeTodo} />

<TodoFilter {remaining} {setFilter} {clearCompleted} />You have to bind each todo to the todos array:

<script lang="ts">

import TodoItem from './TodoItem.svelte'

// ...

let { todos = $bindable(), removeTodo }: Props = $props()

</script>

<ul>

{#each todos as todo, i (todo)}

<li transition:slide>

<TodoItem bind:todo={todos[i]} {removeTodo} />

</li>

{/each}

</ul>For this reason, you should avoid mutating props to avoid unexpected state changes. You can use a callback prop instead, to update a value from a child component.

Let’s update the <Todos> component to use callback props:

<script lang="ts">

function addTodo(e: SubmitEvent) {

e.preventDefault()

const formData = new FormData(this)

todos.push({

id: crypto.randomUUID(),

text: formData.get('todo'),

completed: false

})

this.reset()

}

function toggleTodo(todo: Todo) {

const index = todos.findIndex((t) => t.id === todo.id)

todos[index].completed = !todos[index].completed

}

function updateTodo(todo: Todo) {

const index = todos.findIndex((t) => t.id === todo.id)

todos[index].text = todo.text

}

// ...

</script>

<AddTodo {addTodo} />

<TodoList todos={filteredTodos} {toggleTodo} {updateTodo} {removeTodo} />

<TodoFilter {remaining} {setFilter} {clearCompleted} />The last thing to do is to update the rest of the components to accept callback props:

<script lang="ts">

// ...

let { addTodo }: Props = $props()

</script>

<form onsubmit={addTodo}>

<input type="text" placeholder="Add todo" name="todo" />

</form><script lang="ts">

import TodoItem from './TodoItem.svelte'

// ...

let { todos, toggleTodo, updateTodo, removeTodo }: Props = $props()

</script>

<ul>

{#each todos as todo (todo)}

<TodoItem {todo} {toggleTodo} {updateTodo} {removeTodo} />

{/each}

</ul><script lang="ts">

import { slide } from 'svelte/transition'

// ...

let { todo, toggleTodo, updateTodo, removeTodo }: Props = $props()

</script>

<li transition:slide>

<input

type="checkbox"

checked={todo.completed}

onchange={() => toggleTodo(todo)}

/>

<input

type="text"

value={todo.text}

oninput={() => updateTodo(todo)}

/>

<button onclick={() => removeTodo(todo)}>🗙</button>

</li>You should avoid creating components if you’re not sure what to turn into a component. Instead, write everything inside a single component until it gets complicated, or the reusable parts become obvious.

Later we’re going to learn how to talk between components without props, using the context API.

Component Composition

You can compose components through nesting and snippets which hold content that can be passed as props to components similar to slots. Components can also talk to each other through the context API without props or events.

Component Nesting

In HTML, you can nest elements inside other elements:

<div class="accordion">

<div class="accordion-item">

<button>

<div>Item A</div>

<div class="accordion-trigger">👈️</div>

</button>

<div class="accordion-content">Content</div>

</div>

</div>The fun part of using a framework like Svelte is that you get to decide how you want to compose components. To show component composition in Svelte, let’s create an accordion component that can have many accordion items.

Let’s create these files inside an accordion folder:

accordion/

├── Accordion.svelte

├── AccordionItem.svelte

└── index.tsLet’s export the accordion components from the index.ts file:

export { default as Accordion } from './Accordion.svelte'

export { default as AccordionItem } from './AccordionItem.svelte'Components accept attributes like regular HTML elements called properties, or props* for short. Any content inside the component tags becomes part of the implicit children prop:

<script lang="ts">

import { Accordion, AccordionItem } from './accordion'

</script>

<Accordion>

<!-- children -->

<p>Accordion item</p>

</Accordion>The children prop is actually a snippet which you can define yourself:

<script lang="ts">

import { Accordion, AccordionItem } from './accordion'

</script>

<Accordion>

{#snippet children()}

<p>Accordion item</p>

{/snippet}

</Accordion>Snippets are great for reusing markup, or delegating rendering to a child component.

You can get the children from the $props rune, and render them using the @render tag using an {#if ...} block with a fallback, or optional chaining:

<script lang="ts">

let { children } = $props()

</script>

<div class="accordion">

<!-- using a conditional with a fallback -->

{#if children}

{@render children()}

{:else}

<p>Fallback content</p>

{/if}

<!-- using optional chaining -->

{@render children?.()}

</div>The <AccordionItem> accepts a title prop, and we can show the accordion item content using the children prop which acts like a catch-all for any content inside the component:

<script lang="ts">

import { slide } from 'svelte/transition'

import type { Snippet } from 'svelte'

interface Props {

title: string

children: Snippet

}

let { title, children }: Props = $props()

let open = $state(false)

function toggle() {

open = !open

}

</script>

<div class="accordion-item">

<button onclick={toggle} class="accordion-heading">

<div>{title}</div>

<div class="accordion-trigger" class:open>👈️</div>

</button>

{#if open}

<div transition:slide class="accordion-content">

{@render children?.()}

</div>

{/if}

</div>

<style>

.accordion-item {

&:not(:last-child) {

margin-bottom: var(--spacing-24);

}

.accordion-heading {

display: flex;

gap: 2rem;

padding: 0;

border: none;

}

.accordion-trigger {

transition: rotate 0.2s ease;

&.open {

rotate: -90deg;

}

}

.accordion-content {

margin-top: 0.5rem;

}

}

</style>That’s it! 😄 You can now use the <Accordion> component in your app.

That being said, this has limited composability if you want to change the icon, or position of the individual accordion elements.

Before you know it, you end up with an explosion of props:

<script lang="ts">

import { Accordion, AccordionItem } from './accordion'

</script>

<Accordion>

<AccordionItem

title="Item A"

icon="👈️"

iconPosition="left"

...

>

Content

</AccordionItem>

</Accordion>That’s not a way to live your life! Instead, you can use inversion of control so the user can render the accordion item however they want.

Snippets

Let’s modify the <AccordionItem> component to accept an accordionItem snippet as a prop instead, and pass it the open state and toggle function, so we have access to them inside the snippet:

<script lang="ts">

import type { Snippet } from 'svelte'

interface Props {

accordionItem?: Snippet<[accordionItem: { open: boolean; toggle: () => void }]>

}

let { accordionItem }: Props = $props()

let open = $state(false)

function toggle() {

open = !open

}

</script>

<div class="accordion-item">

{@render accordionItem?.({ open, toggle })}

</div>You can define and render a snippet in your component for markup reuse, or delegate the rendering to another component by passing it as a prop:

<script lang="ts">

import { slide } from 'svelte/transition'

import { Accordion, AccordionItem } from './accordion'

</script>

{#snippet accordionItem({ open, toggle })}

<button onclick={toggle} class="accordion-heading">

<div>Item A</div>

<div class="accordion-trigger" class:open>👈️</div>

</button>

{#if open}

<div transition:slide class="accordion-content">

Content

</div>

{/if}

{/snippet}

<Accordion>

<AccordionItem {accordionItem} />

</Accordion>You can create an implicit prop by using a snippet inside the component tags. In this example, the accordionItem snippet becomes a prop on the component:

<script lang="ts">

import { slide } from 'svelte/transition'

import { Accordion, AccordionItem } from './accordion'

</script>

<Accordion>

<AccordionItem>

{#snippet accordionItem({ open, toggle })}

<button onclick={toggle} class="accordion-heading">

<div>Item A</div>

<div class"accordion-trigger" class:open>👈️</div>

</button>

{#if open}

<div transition:slide class="accordion-content">

Content

</div>

{/if}

{/snippet}

</AccordionItem>

</Accordion><script module> if they don't reference any state in a script block, and use them in other components.This gives you complete control how the accordion item is rendered.

The Context API